Info

This is a summary of the sixth chapter of the book “Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces” by Remzi H. Arpaci-Dusseau and Andrea C. Arpaci-Dusseau. The chapter covers the concept of limited direct execution, which allows user programs to run directly on the CPU while ensuring the operating system retains control over privileged operations. Key topics include system calls, traps, kernel mode, user mode, and context switching.

How to efficiently virtualize the CPU with control?

What is Direct Execution?

Direct Execution means to run a program directly on the CPU. For an OS to not behave as a standard library, it should have restrictions on system calls.

System calls are just normal procedural calls written carefully in Assembly, as they need to carefully follow convention in order to proceed arguments and return values correctly. So what if the process wishes to perform some kind of restricted operation, such as issuing an I/O request to a disk, or gaining access to more system resources such as CPU or memory?

This is where the Limited part of Limited Direct Execution comes in. For a more secure system call we are going to implement two new features in the OS:

- User and Kernel Mode

- Using trap table

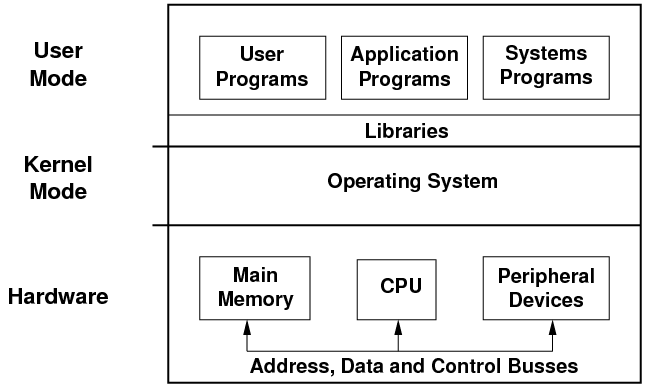

Code that runs in user mode is restricted in what it can do. For example, when running in user mode, a process can’t issue I/O requests; doing so would result in the processor raising an exception; the OS would then likely kill the process. In contrast to user mode is kernel mode, which the operating system (or kernel) runs in. In this mode, code that runs can do what it likes, including privileged operations such as issuing I/O requests and executing all types of restricted instructions.

Using Protected Control Transfer

To execute a system call, a program must execute a special trap instruction. This instruction simultaneously jumps into the kernel and raises the privilege level to kernel mode; once in the kernel, the system can now perform whatever privileged operations are needed (if allowed), and thus do the required work for the calling process. When finished, the OS calls a special return-from-trap instruction, which, as you might expect, returns into the calling user program while simultaneously reducing the privilege level back to user mode.

How to switch between Processes? How to regain control of the CPU?

Cooperative approach:

give a process control of the CPU and hope it doesn’t end in an infinite loop. The process also lets the OS do the System calls.

How to gain control without cooperation?

A timer interrupt. A timer device can be programmed to raise an interrupt every so many milliseconds; when the interrupt is raised, the currently running process is halted, and a pre-configured interrupt handler in the OS runs. At this point, the OS has regained control of the CPU, and thus can do what it pleases: stop the current process, and start a different one.

Dealing with application misbehaviour:

In modern systems, the way the OS tries to handle such malfeasance is to simple terminate the offender. “One strike and you’re out!”

Context-Switching:

Process A is running and then is interrupted by the timer interrupt. The hardware saves its registers (onto its kernel stack) and enters the Kernel Mode. In the timer interrupt handler, the Os decides to switch from running process A to process B. At that point, it calls the switch() routine, which carefully saves current register values (into the process structure of A), restores the registers of process B, and then switches contexts, specifically by changing the stack pointer to use B’s registers and starts running it.

Baby proofing:

First (during boot time) setting up the trap handler and and storing an interrupt timer, and then by only running processes in a restricted mode. By doing so, the OS can feel quite assured that processes can run efficiently, only requiring OS intervention to perform privileged operations or when they have monopolized the CPU for too long and thus need to be switched out.

Crucial Questions:

Why is the trap instruction essential for both security and performance in CPU virtualization, and how does it ensure the OS remains in control during system calls?

Security:

- The CPU operates in two modes: user mode (restricted) and kernel mode (privileged). User-mode programs cannot perform sensitive operations like accessing hardware (e.g., disk, memory) directly because that would compromise system security.

- The Trap Instruction allows a user-mode program to request a privileged operation from the OS safely. When a program makes a system call (e.g., reading a file), it uses a Trap Instruction to switch from user mode to kernel mode.

- The OS, running in kernel mode, can now securely perform the requested operation. Once the task is completed, the OS returns control to the program in user mode. This mechanism ensures that programs can only request system resources through the OS, maintaining strict control and protecting the system from unauthorized access.

Performance:

- Without traps, the OS would need to simulate everything (like hardware access), which would be slow and inefficient. The Trap Instruction allows user-mode programs to run directly on the CPU at full speed while giving the OS control only when needed (like during system calls).

- The trap table, which the OS sets up during boot, tells the CPU what to do when a trap occurs. This allows the OS to quickly handle system calls, exceptions, and interrupts in an efficient, predefined way.

- By letting the program run natively on the CPU most of the time and only trapping into kernel mode when necessary, performance is maximized while maintaining the OS’s control.

What challenges arise in handling context switches during nested system calls or interrupts, and how does the OS manage these complexities without causing errors or inefficiencies?

A context switch happens when the OS stops one process and switches to another. The OS must save the state of the current process (its context, like registers, program counter, etc.) and load the state of the next process to resume its execution. This seems straightforward, but things get complex in the following cases:

Challenges:

-

Nested Interrupts: Imagine a situation where the OS is handling a system call (i.e., it’s already in kernel mode), and in the middle of that, a timer interrupt occurs or another system call is made. The OS must deal with multiple layers of context switching.

- If the OS doesn’t manage this properly, it might lose the original context (the registers and state of the first process), leading to errors when trying to resume it later.

-

Interrupt During System Call: During a system call, the OS might be in the middle of performing an important task, like writing to a file. If an interrupt occurs (e.g., the timer interrupt), the OS needs to pause what it’s doing, handle the interrupt (potentially switch to another process), and then return to complete the original system call without losing data or creating inconsistencies.

-

Concurrency: Modern systems handle multiple processes, often on multiple CPUs, which means that context switching needs to be efficient and well-coordinated to avoid race conditions (when two processes try to modify the same data at the same time) or deadlocks (where two processes wait on each other indefinitely).

How the OS Manages These Complexities:

- Kernel Stack: Each process has its own kernel stack, which stores the context (registers, program counter, etc.) when it traps into the OS or when an interrupt occurs. This allows the OS to pause a process, handle an interrupt, and then later resume the process by restoring its state from the kernel stack.

- Nested Interrupt Handling: The OS must be careful when interrupts occur during other interrupts or system calls. One strategy is to disable further interrupts while handling the current interrupt to avoid confusion. However, modern systems may also allow interrupt prioritization, where higher-priority interrupts can pre-empt lower-priority ones.

- Saving State Carefully: When an interrupt or system call occurs, the hardware (like the CPU) automatically saves certain critical registers (such as the program counter) onto the process’s kernel stack. This allows the OS to handle the interrupt or system call and then resume the interrupted process at the exact point it left off.

- Context Switching Code: The OS’s context-switching code, which runs in kernel mode, is written very carefully to ensure all necessary registers are saved before switching to another process. When switching back, the saved context is restored so that the process can continue as if nothing happened.